A Critical Review of Ron Chernow’s “Grant”

An American Sphinx: The Puzzle of Grant’s Legacy

There are figures in the historical pageant of a nation who seem forged from its very bedrock—solid, unambiguous, their virtues and vices etched in high relief. Washington was the stoic father, Lincoln the martyred savior, Roosevelt the aristocratic force of nature. And then there is Ulysses S. Grant. For over a century, Grant has been America’s great enigma, a man whose historical memory has been as contested and contradictory as the Civil War he won. He is the military butcher of the Overland Campaign and the magnanimous peacemaker at Appomattox. He is the drunkard fumbling his way to failure in dusty frontier outposts and the resolute commander who saved the Union. He is the naïve political incompetent presiding over a Gilded Age administration synonymous with corruption, and the fierce, forward-thinking president who crushed the first Ku Klux Klan and championed the rights of four million newly freed slaves. How can all these men be the same man? This is the central, haunting question that has shadowed Grant’s legacy, making him less a historical figure and more a canvas onto which successive generations have projected their own anxieties about the American experiment.

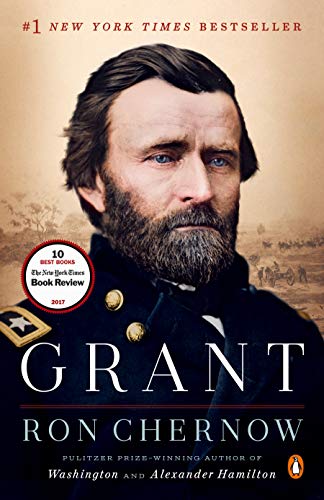

Into this historiographical fray steps Ron Chernow, a biographer who has made a career of dusting off the monumental statues of American history and reminding us of the complex, often fragile, humans who dwell within. With his Pulitzer Prize-winning Washington: A Life and the culture-shifting Alexander Hamilton, Chernow has established himself as the master excavator of the American founder’s soul, blending meticulous research with a novelist’s eye for narrative and psychological depth. With Grant, he undertakes arguably his most ambitious and necessary project of historical reclamation. The book is, on its surface, a monumental, cradle-to-grave biography in the grand tradition. Yet to read it as such is to miss its true purpose. This is not merely a work of chronicling; it is a work of resurrection. Chernow’s implicit argument, woven through a thousand pages of dense but lucid prose, is that the century-long campaign to diminish Grant was no accident. It was, rather, a direct and insidious consequence of the “Lost Cause” ideology—a systematic effort by defeated Confederates and their sympathizers to rewrite the history of the Civil War, transforming a struggle over slavery into a noble tragedy and, in the process, vilifying the Northern general who had the audacity to win it and the president who tried to enforce the radical consequences of that victory.

This review, however, will argue for a deeper reading of Chernow’s achievement. While the book is an undeniable triumph of historical revisionism, its most profound contribution is not political but literary. Chernow’s ultimate success lies not in the unearthing of new facts, but in his radical reconstruction of Grant’s interior world. He takes on the monumental challenge of animating a man famous for his impenetrable stoicism and laconic prose. Where others saw a simple, brutish man—an “unlikely vessel,” as Chernow calls him—he finds a deep reservoir of sensitivity, a crippling shyness, an abiding intellect, and a profound emotional core that was the very engine of his improbable rise and his tragic, noble failures. Chernow accomplishes this not by speculating, but by performing a kind of literary archaeology, using Grant’s own famously unadorned words, his letters, and especially his sublime Personal Memoirs, as the primary evidence. He demonstrates that the plainness of Grant’s style was not a sign of a simple mind, but the mark of a man who wrestled with his own demons and the horrors he witnessed with an honesty so profound it required no rhetorical flourish. This review will therefore analyze Grant not just as a corrective to a flawed historical narrative, but as a masterclass in the art of biographical interpretation, where the biographer’s greatest tool is his ability to read the silences between the words and to find the soul of his subject in the very grammar of his stoicism. We will explore how Chernow builds his case brick by evidentiary brick, dismantling the caricature of the “butcher” and the “corrupt” president, before advancing our own central thesis: that Chernow’s Grant is ultimately a profound meditation on the relationship between character and destiny, and a literary argument that the quiet, unassuming virtues of one man very nearly saved the soul of a nation.

The Shadow of the Lost Cause: Context and Chernow’s Method

To understand the magnitude of what Ron Chernow accomplishes in Grant, one must first grasp the depths from which he is rescuing his subject. The Ulysses S. Grant that generations of Americans came to know was a figure largely invented in the late 19th and early 20th centuries by a concerted propaganda campaign. The “Lost Cause of the Confederacy” was more than just a nostalgic lament for a defeated South; it was a powerful and pervasive cultural and historical movement designed to reframe the narrative of the Civil War. It sought to erase slavery as the central cause of the conflict, romanticize Confederate leaders like Robert E. Lee as chivalrous Christian knights, and portray the antebellum South as a pastoral utopia. For this mythology to succeed, it required a villain—a figure who embodied the North’s supposed barbarism, industrial soullessness, and vindictive spirit. Ulysses S. Grant was tailor-made for the role.

His military strategy, predicated on relentless pressure and a grim acceptance of attrition, was recast not as strategic genius but as brutish butchery. He was contrasted unfavorably with the impeccably dressed and seemingly infallible Lee, ignoring the fact that Grant consistently out-thought and out-maneuvered him. Grant’s presidency, which followed the war, became the second front in this historical assault. The Dunning School of historians, which dominated Reconstruction scholarship for decades, portrayed this period as a tragic mistake. They argued that Radical Republican attempts to enforce black suffrage and civil rights were a foolish and corrupt imposition on a prostrate South. In this narrative, Grant was the hapless, incompetent president, a well-meaning simpleton manipulated by corrupt cronies, whose efforts to protect African Americans from groups like the Ku Klux Klan were a tyrannical overreach. This interpretation conveniently ignored the widespread terrorism and violence being inflicted on Black citizens and their white allies. The result was the near-total demolition of Grant’s reputation. By the mid-20th century, he was consistently ranked among the worst American presidents, his military triumphs dismissed as products of brute force, not brilliance.

It is this historical landscape that Chernow enters. His method is one of total immersion, built on a foundation of exhaustive primary source research. But his genius is not merely in accumulation; it is in synthesis and psychological portraiture. Unlike a purely academic historian who might focus on a narrow aspect of Grant’s life, Chernow is a narrative biographer in the tradition of David McCullough or Robert Caro. His goal is to tell a story, to make the past live and breathe. He does this by focusing on character. Chernow’s operating principle across his works is that character is destiny. He believes that to understand the historical actions of figures like Hamilton, Washington, or Grant, we must first understand their innermost anxieties, their family dynamics, their formative experiences, and their emotional constitution.

In the case of Grant, this approach is both essential and incredibly difficult. Grant left behind no soul-searching diaries. His letters are often practical and reserved. His public persona was one of almost painful reticence. Chernow’s method is to turn this apparent liability into his central analytical tool. He performs what can only be described as a close reading of Grant’s life, treating his actions, his relationships, and his sparse words as a text to be interpreted. He leans heavily on two key sources: the loving, insightful letters of Grant’s wife, Julia, who understood her husband’s hidden depths better than anyone, and Grant’s own Personal Memoirs, written with superhuman courage as he was dying of throat cancer. Chernow dissects the Memoirs not just for their content but for their style. He argues that the famous clarity, precision, and humility of Grant’s prose are a direct reflection of his mind. They reveal a man of supreme confidence, intellectual honesty, and a fundamental decency that was the bedrock of his character. Chernow’s premise is that the historical caricature of Grant could only exist if one refused to actually read Grant himself. By taking Grant’s words and actions seriously, and by placing them in the carefully reconstructed context of his time, Chernow dismantles the Lost Cause mythology not with polemics, but with a relentless accumulation of evidence, allowing Grant’s true character to emerge from the historical fog.

The Evidentiary Chain: Reconstructing a Life

Chernow’s case for Grant is built upon a meticulous, almost legalistic, presentation of evidence. He does not simply assert a new interpretation; he guides the reader through the primary sources that lead him to it, forcing us to confront the stark disparity between the myth and the man. This core analysis can be understood through three pillars of evidence Chernow painstakingly erects: the reframing of Grant’s military career, the reassessment of his presidency, and the revelation of his inner life.

Pillar One: The General as Strategist, Not Butcher

The most persistent slander against Grant’s name is that of the “butcher.” The charge stems primarily from the brutal 1864 Overland Campaign, where the Union Army suffered staggering casualties in a relentless drive toward Richmond. Lost Cause historians framed this as a mindless application of overwhelming force, contrasting it with the supposed tactical finesse of Robert E. Lee. Chernow dismantles this by marshaling two forms of evidence: a detailed operational analysis of the campaign and, more importantly, Grant’s own private correspondence which reveals his profound anguish over the human cost of his decisions.

First, Chernow meticulously re-litigates the military situation in the spring of 1864. He shows that, unlike his predecessors, Grant had a comprehensive, theater-wide strategy to engage all Confederate armies simultaneously, preventing them from reinforcing one another. The Overland Campaign was the bloody centerpiece of this strategy. Chernow quotes Grant’s own clear-eyed assessment: “I determined… to use the greatest number of troops practicable against the armed force of the enemy, preventing him from using the same force at different seasons against first one and then another of our armies and the possibility of repose for refitting and producing necessary supplies for carrying on resistance.” This was not butchery; it was a coherent and ultimately successful theory of victory against a determined foe. Chernow then takes us into the details of battles like the Wilderness and Spotsylvania Court House. He highlights Grant’s flexibility and tactical creativity in the face of horrific conditions, a far cry from the myth of a general who simply threw bodies at fortifications.

The second, and more powerful, layer of evidence comes from Grant’s own pen, revealing the man behind the strategy. After the horrific slaughter at Cold Harbor, an attack he later admitted was a grave mistake, Grant’s humanity shines through the historical accounts Chernow selects. He quotes a letter Grant wrote to his wife Julia, a piece of evidence that directly refutes the caricature of a callous butcher: “Oh, Julia, I have had a very, very hard time of it since you left. The anxieties of the position I feel, but not so much as the sufferings of the poor men who do the fighting.” Chernow lingers on such passages, forcing the reader to see the emotional toll of command. He supplements this with testimony from Grant’s staff, like aide Horace Porter, whom Chernow quotes describing Grant’s reaction to a wounded soldier: “The general, whose eyes were moist with tears, dismounted, and taking the man’s hand, said to him in a voice of pathetic tenderness, ‘I am sorry to see you in this condition, my man, and I hope you will soon be all right.'” By juxtaposing the grim strategic necessity with Grant’s deep, personal empathy, Chernow doesn’t just excuse the casualties; he reframes them as the tragic but necessary price of a victory that Grant himself felt more keenly than anyone. He replaces the one-dimensional caricature with a complex portrait of a leader grappling with the horrific moral calculus of war.

Pillar Two: The President as Civil Rights Champion

If Grant’s military career was distorted, his presidency was subjected to outright character assassination. The Dunning School narrative painted his two terms as a nadir of American governance, defined by corruption and a misguided, tyrannical “Negro rule” in the South. Chernow’s revision of the Grant presidency is perhaps the most vital part of the book, and he builds his case on the bedrock of Grant’s decisive, and historically neglected, actions in defense of African American rights.

The primary evidence here is Grant’s war against the first Ku Klux Klan. Chernow presents Grant not as a passive observer, but as the active, driving force behind the federal government’s most significant effort to protect civil rights for a century. He details how Grant, personally outraged by the Klan’s terrorist campaign of murder, intimidation, and voter suppression, pushed a reluctant Congress to pass the Force Acts of 1870 and 1871. These landmark pieces of legislation gave the president the power to use federal troops to suppress conspiracies, suspend habeas corpus, and enforce the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. Chernow provides the damning evidence of the Klan’s brutality through congressional reports and eyewitness testimonies that Grant himself read, emphasizing the moral conviction that drove the president. He then quotes directly from Grant’s communications, showing his determination. To his Attorney General, Amos Akerman, Grant wrote with unambiguous force: “I am extremely anxious to see a conviction of some of these parties. It is a disgrace to any civilized country that such a state of affairs should exist.”

Chernow then chronicles the results of this determination. He details how Grant, using the new laws, sent federal troops into South Carolina and other hotbeds of Klan activity, smashing the organization and arresting thousands of its members. It was a stunning, and sadly temporary, success. To counter the narrative of incompetence, Chernow shows a president who was engaged, decisive, and morally clear. Regarding the issue of corruption, Chernow doesn’t whitewash it. He meticulously documents the scandals, like the Whiskey Ring, that plagued the administration. However, he presents compelling evidence that the corruption was a feature of the era’s political culture, not of Grant’s character. The evidence he uses is Grant’s own reaction to the scandals. When his own private secretary, Orville Babcock, was implicated, Grant’s first instinct was to defend a man he considered a friend. But Chernow also presents the evidence of Grant’s famous deposition in the case—an unprecedented act for a sitting president—and his agonized, handwritten note: “Let no guilty man escape.” Chernow’s analysis of this evidence suggests a man whose greatest political flaw was not a lack of morals, but an excess of loyalty—a personal virtue that proved to be a public liability. He was a man whose decency made him vulnerable to the schemes of lesser men, a far more tragic and believable portrait than that of a corrupt mastermind or a clueless simpleton.

Pillar Three: The Evidence of the Interior World

The final and most original pillar of Chernow’s evidentiary structure is his deep dive into Grant’s inner life. He seeks to answer the question: who was this quiet man? His primary evidence is Grant’s most personal relationships and his own literary masterpiece, the Personal Memoirs. Chernow argues that Grant’s notorious reticence was not a sign of a vacant mind but of a profound and often painful shyness, rooted in a difficult childhood with a demanding father. The key that unlocks this inner world, in Chernow’s telling, is Grant’s relationship with his wife, Julia Dent.

Chernow quotes extensively from Julia’s own memoirs and their private correspondence, which he treats as a Rosetta Stone for Grant’s soul. These letters reveal a side of Grant hidden from almost everyone else: a tender, loving, and deeply dependent husband. He presents passages of surprising emotional vulnerability, such as a young Grant writing to his fiancée: “You can have but little idea of the influence you have over me, Julia, even while so far away. If I feel tempted to do anything that I think is not right, I am sure to think, ‘Well, now, if Julia saw me, would I do so?’ and at once I answer to myself NO.” This is not the voice of a stolid, unfeeling warrior. Chernow uses this evidence to argue that Julia’s unconditional love and belief in him were the essential foundation of his success. She was the one person with whom he could drop his emotional guard, and her presence was the anchor that stabilized his often-turbulent life.

The capstone of Chernow’s evidence is his brilliant analysis of the Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant. He treats the book not merely as a historical source, but as a profound act of self-revelation. He asks the reader to consider the sheer force of character required to write such a book—over 300,000 words of lucid, precise, and magnanimous prose—while in excruciating pain and racing against death to provide for his family. For Chernow, the style of the Memoirs is the ultimate proof of the man’s substance. He contrasts Grant’s unadorned, direct prose with the florid, self-aggrandizing style common in 19th-century memoirs. He quotes a classic Grant passage, describing the surrender at Appomattox: “I felt sad and depressed at the downfall of a foe who had fought so long and valiantly, and had suffered so much for a cause, though that cause was, I believe, one of the worst for which a people ever fought.” Chernow dissects this sentence, pointing to its extraordinary balance of empathy for the defeated soldiers and unflinching moral clarity about their cause. There is no gloating, no vanity—only a sober, honest assessment. For Chernow, this prose is the man. The honesty, decency, and quiet intelligence that generations of historians claimed Grant lacked were there all along, hiding in plain sight, in the magnificent sentences of his own final testament.

The Literary Resurrection: Chernow’s Grant as a Novelistic Creation

While Ron Chernow’s Grant is a triumph of historical revisionism, its most audacious and enduring achievement is fundamentally literary. The central thesis of this review is that Chernow’s book transcends the genre of biography and operates as a work of literary resurrection. He accomplishes something more profound than simply correcting the historical record; he resurrects a soul. He takes Ulysses S. Grant—a figure flattened into a caricature by a century of historical malpractice, a man defined by his own impenetrable stoicism—and reveals the rich, turbulent, and deeply sensitive inner life that the granite exterior was built to protect. He does this not by inventing or speculating in the manner of a historical novelist, but by deploying a biographer’s tools with a novelist’s sensibility. He treats Grant’s life as a narrative text, his silences as subtext, and his famously plain prose as the most powerful evidence of a complex mind. Chernow’s greatest creation in this book is not a new set of facts, but a fully realized, psychologically coherent, and deeply moving character.

The first step in this literary resurrection is Chernow’s framing of Grant’s life as a classic narrative of the unlikely hero. The pre-war Grant is a figure of almost pathetic failure. Chernow lingers on these wilderness years: the struggles with alcohol, the loneliness of frontier posts, the humiliation of having to resign from the army, the poverty that forced him to sell firewood on the streets of St. Louis. A conventional historian might summarize these years as a necessary prelude. Chernow, however, renders them with novelistic detail and empathy. He wants the reader to feel the full weight of Grant’s despair, to understand the psychic wounds he carried. This makes his sudden, explosive rise during the Civil War not just a historical event, but a profound character transformation. Chernow implicitly poses a novelist’s question: what was it about this specific man, this quiet failure, that allowed him to succeed where so many more credentialed and celebrated generals had failed?

The answer, Chernow argues through his narrative construction, lies in the very qualities that had been perceived as weaknesses. His quietness was not stupidity, but the mark of a man who listened more than he spoke, who observed, and who thought deeply. His lack of pretension and his simple, direct manner allowed him to see problems with a clarity that eluded more arrogant commanders. His experience with failure gave him a humility and a resilience that others lacked. Chernow builds this character portrait through carefully chosen anecdotes and the testimony of others. He quotes Lincoln’s famous, folksy defense of his general: “I can’t spare this man; he fights.” But Chernow pushes deeper, showing why he fought so effectively. He reconstructs Grant’s thought processes before key battles, showing a mind that was methodical, logical, and capable of holding immense complexity in its grasp. The effect is to transform Grant from a historical actor into a compelling protagonist. We are not just told that he was a genius; we are invited into his mind to witness that genius at work.

The most potent tool in this literary project is Chernow’s use of Grant’s own writing. He understands that the Personal Memoirs are not just a source, but the climax of Grant’s life story. The final section of the biography, detailing Grant’s heroic battle against cancer to complete the book, is rendered with breathtaking pathos. Chernow portrays it as Grant’s last and greatest battle. Here, the biographer’s voice and the subject’s voice merge. Chernow analyzes passages from the Memoirs with the same care a literary critic would devote to a great novel. He shows how Grant’s refusal to speak ill of his rivals, his generosity to his foes, and his unflinching honesty about his own mistakes are not just stylistic choices, but moral and ethical ones. They are the final, definitive evidence of the man’s true character. By focusing so intensely on the act of writing, Chernow suggests that Grant ultimately defined himself not on the battlefield or in the White House, but on the page. In doing so, Chernow elevates his subject from a great general to a great American writer, a figure whose moral substance is inseparable from his literary style. This is the heart of the resurrection. Chernow proves that to truly understand Grant, you must read him, and to read him is to know him. The book is, therefore, less a traditional biography and more of a profound critical appreciation, an argument that Grant’s greatest legacy might be the quiet, honest, and deeply humane voice he left behind.

The Unfinished War: Grant’s Resonance in Contemporary America

A great work of history does more than illuminate the past; it speaks directly to the present. Ron Chernow’s Grant is such a work. To read it in the 21st century is to be struck by the haunting and urgent relevance of Grant’s struggles. The book is not merely a biography of a 19th-century general and president; it is an autopsy of a nation’s original sin and its fraught, unfinished battle for its own soul. The political and social conflicts that defined Grant’s era—battles over voting rights, racial justice, domestic terrorism, and the very meaning of American citizenship—are not relics of a distant past. They are the foundational conflicts that continue to shape American life today. Chernow’s masterpiece serves as both a powerful origin story for our current divisions and a cautionary tale about the fragility of progress.

The most potent contemporary echo is found in Chernow’s meticulous account of the Reconstruction era. This period, so often glossed over in popular American history, emerges in Grant as the crucial turning point where the promise of the Civil War was won and then lost. When Grant took office, he presided over a nation wrestling with the revolutionary implications of emancipation. For a brief, radical moment, the federal government, under Grant’s leadership, was committed to protecting the rights of its new African American citizens. As Chernow documents, Grant used the power of the state to crush the Ku Klux Klan, safeguard Black voters, and prosecute those who sought to reimpose a form of slavery through violence and intimidation. Reading this account today, in an era marked by renewed struggles over voter suppression and the rise of politically motivated violence, is a startling and sobering experience. It reveals that the fight to ensure a truly multiracial democracy is not new, but is in fact one of the oldest and most central conflicts in American history. Grant’s presidency stands as a powerful testament to what is possible when federal power is wielded in the name of justice and equality.

However, the book is also a tragedy. Chernow painfully chronicles how the North gradually lost its will to continue the fight for Reconstruction. A combination of economic crisis, political fatigue, and resurgent racism led to a retreat from the promises made in the wake of the war. The “redemption” of the South by white supremacists, the rise of Jim Crow, and the erasure of Black political power were the direct results. This historical narrative provides a crucial context for understanding the deep roots of systemic inequality in America. It reminds us that progress is not inevitable and that hard-won rights can be swiftly lost when vigilance wanes. The failure of Reconstruction, as detailed in Grant, cast a long shadow that stretches into the present day, creating the very conditions of racial and economic disparity that remain the nation’s most pressing challenge.

So, who is the ideal reader for this monumental book? On one level, it is for anyone who enjoys immersive, narrative history at its finest. Chernow is a master storyteller, and the book is a compelling epic filled with dramatic battles, political intrigue, and a deeply human protagonist. But on a deeper level, the ideal reader is the citizen who wishes to understand the fractured state of America today. Is [Grant] good? is a question the search engines might ask. The answer is an unequivocal yes, but not because it is merely a good story. It is a necessary book. It is for the reader who wants to understand why the Civil War never truly ended, why the arguments of 1868 feel so eerily similar to the arguments of today. It is for anyone who believes in the power of character, decency, and quiet determination in leadership. Grant’s life, with its stunning triumphs and heartbreaking failures, serves as a mirror. In it, we see the best of what America can be—its capacity for moral courage and transformation—and the worst of its failures, its tragic inability to live up to its own founding ideals. Chernow’s book is not just a history; it is an essential guide to the unfinished business of being an American.

The Final Victory: A Lasting Testament

In the final accounting, Ron Chernow’s Grant stands as a masterwork of the biographical form, a book that is as sweeping in its historical scope as it is intimate in its psychological portraiture. It achieves that rarest of feats: it not only reshapes our understanding of a pivotal historical figure but also forces us to re-examine the narrative of the nation itself. Chernow successfully prosecutes the case for Grant’s greatness, dismantling the calumnies of the Lost Cause with a relentless barrage of meticulously researched evidence. He restores Grant to his rightful place in the American pantheon, not as a plaster saint, but as a complex, flawed, and profoundly decent man who met his moment with a courage and clarity of vision that saved the Union and then fought desperately to redefine it.

The book’s ultimate power, however, lies in its quiet insistence on the primacy of character. In an age that often celebrates the loudest voice and the most flamboyant personality, Chernow presents a hero of a different sort. Grant was shy, unassuming, and often wracked with self-doubt. He was a man of simple tastes who was uncomfortable in the spotlight. Yet, within this quiet exterior resided an iron will, a superior intellect, and an unshakable moral core. His story is a powerful reminder that true strength is often found not in bombast, but in resilience; not in arrogance, but in humility; not in the pursuit of personal glory, but in a quiet, dogged dedication to a cause greater than oneself.

Chernow’s final, moving chapters on the writing of the Personal Memoirs serve as a perfect coda. In this last act, Grant achieves a victory more profound than any on the battlefield. Facing death, stripped of his fortune by swindlers, he summons his remaining strength to tell his own story with an honesty and magnanimity that is almost superhuman. In doing so, he provides for his family and leaves behind a literary monument that is the final, irrefutable proof of his character. Chernow’s biography is, in a sense, a conversation with that great memoir. It amplifies its truths, explains its context, and channels its spirit. It completes the work that Grant began, ensuring that the voice of this quiet, essential American can once again be heard, clear and true, above the noise of a century of distortion. Grant is more than a great biography; it is an act of historical justice and a lasting testament to the unlikely, unassuming, and undeniable greatness of Ulysses S. Grant.

FAQ Section

Q1: What is Ron Chernow’s book “Grant” about?

A1: Ron Chernow’s “Grant” is a comprehensive biography of Ulysses S. Grant, the 18th President of the United States and commanding general of the Union Army during the Civil War. The book aims to rehabilitate Grant’s reputation, arguing that he was a brilliant and humane general, a courageous (if flawed) president who championed civil rights, and a man of profound decency and character.

Q2: Is “Grant” by Ron Chernow historically accurate?

A2: Yes, “Grant” is widely praised by historians for its meticulous research and historical accuracy. Chernow draws extensively from primary sources, including Grant’s personal letters, the memoirs of those who knew him, and official records, to challenge and correct long-standing myths and inaccuracies about his life and career.

Q3: What are the main themes of the book “Grant”?

A3: The main themes include the nature of leadership and character, the brutal realities of war, and the tragic failure of Reconstruction. A central theme is the “Lost Cause” myth and how it systematically destroyed Grant’s reputation as part of an effort to rewrite the history of the Civil War. The book explores Grant’s personal struggles with failure and alcohol, his deep love for his wife Julia, and his ultimate triumph of character in writing his memoirs.

Q4: Is Ron Chernow’s “Grant” worth reading?

A4: Absolutely. For anyone interested in American history, the Civil War, or presidential biographies, “Grant” is considered an essential and masterful work. It is a long and detailed read, but Chernow’s engaging, narrative style makes it accessible. The book is not just a biography but a profound exploration of a pivotal and troubled era in American history that holds deep relevance today.