The Unbreakable, Unbearable Bond

There are friendships, and then there are the gravitational forces that masquerade as friendships. We speak of the latter in hushed, almost mythical terms: the ride-or-die bond, the brother from another mother, the person who knew us before we knew ourselves. These are the relationships forged in the unglamorous crucible of youth, often in the shared soil of lack—lack of money, lack of opportunity, lack of a father. They are not chosen so much as recognized, a sudden, fierce allegiance that feels as preordained and absolute as a law of physics. They provide the scaffolding for an identity, a two-person system against a world that feels hostile or, worse, indifferent. But what happens when that scaffolding becomes a cage? What is the cost of a loyalty so absolute that it eclipses the self? And what becomes of the one left standing when the ride, inevitably and violently, comes to an end?

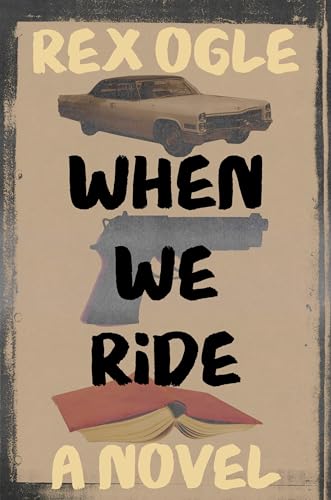

This is the harrowing territory explored by Rex Ogle in his devastatingly beautiful novel in verse, When We Ride. Ogle, an author who has carved a vital niche in young adult literature with his unflinchingly raw and autobiographical works like Free Lunch and Punching Bag, here turns his poetic scalpel to fiction, though the blood on the page feels just as real. When We Ride is not a story you read; it is a story you witness, a post-mortem of a brotherhood so profound it becomes a prophecy of doom. Presented through the eyes of Diego Miguel Benevides, a studious, soft-spoken seventeen-year-old known to all as “Benny,” the novel is a frantic, heartbreaking rewind—a life flashing before his eyes in the split second a gun is pressed to his temple. That life is, in essence, the story of his friendship with Lawson Pierce, the charismatic, reckless, and dangerously alluring boy across the street who has been his other half for a decade.

To ask the simple question that search engines and book clubs so often pose—is When We Ride good?—is to miss the point entirely. The book is not “good” in the way a pleasant afternoon read is good. It is vital. It is necessary. It is an act of radical empathy that transcends its YA categorization to become a piece of profound social commentary on the fracturing of the American dream and the terrifying illusion of individual choice. Ogle’s sparse, percussive verse strips away every ounce of narrative fat, leaving only the bone, muscle, and beating heart of a relationship that is at once life-sustaining and utterly ruinous. The narrative unfolds not as a series of events, but as a collection of memories, each one a polished stone that, when placed in order, paves the road to an inescapable tragedy.

This review, therefore, will not treat When We Ride as a simple cautionary tale. Instead, it will argue that the novel is a modern tragedy in the classical sense, a story not about bad choices, but about the absence of them. Through a deep analysis of the relational dynamics between Benny and Lawson, we will explore how their bond, forged in the shared trauma of paternal abandonment, becomes a closed system from which neither can escape. We will deconstruct how Ogle uses the form of the verse novel to mirror the fragmented, high-stakes rhythm of his characters’ lives. And ultimately, we will contend that Benny’s final, fatal act of sacrifice is not a choice made in a moment of panic, but the only possible conclusion to a life lived in the gravitational pull of another—the terrible, beautiful, and inescapable tyranny of a loyalty that demands everything. This is not just a review of a book by Rex Ogle; it is an autopsy of a brotherhood, an examination of a wound that speaks to the deepest fissures in the landscape of modern youth.

Mapping the Unseen Scaffolding

Before one can dissect the heart of Benny and Lawson’s relationship, one must first understand the world that built them. The setting of When We Ride is an unnamed, unremarkable town that could be anywhere in forgotten America. It is a place of stark, unspoken divisions. There is the world of manicured lawns and two-parent homes where girls like Lori, the salutatorian with a new Mercedes, throw parties. And then there is Benny and Lawson’s neighborhood, a landscape of decay where “Paint flaking off houses like dry skin” and “Bars on windows, like detention centers” are the norm. Ogle’s verse paints this world not with broad strokes but with sharp, incisive details: “Cars on bricks in front yards. / Angry pit bulls barking mad.” This is not merely a backdrop; it is an active character in the novel, an environment that limits, defines, and ultimately suffocates its inhabitants.

Into this world are born two boys, mirror images and perfect opposites. Diego “Benny” Benevides is the book’s anchor, its conscience. Burdened by his mother’s history with alcoholism and her fierce, desperate hope that he will be the first in their family to attend college, Benny is a creature of immense discipline and quiet anxiety. He is the boy who studies during his lunch break, who works a demeaning job busing tables at a diner, and who lies about drinking vodka sodas at parties while sipping on ginger ale. His driving motivation is escape, not just from poverty, but from the genetic and environmental ghosts that haunt him. He tells his mother, who worries about him falling into trouble, “No one can get me in trouble / except me.” It is a statement of desperate self-assurance from a boy who believes, against all evidence, in the power of his own will to chart a different course.

Lawson Pierce is the novel’s supernova—brilliant, captivating, and destined to burn out. He is everything Benny is not: effortlessly charming, physically imposing, and utterly unbound by the rules that govern Benny’s life. While Benny sees education as his only way out, Lawson sees the streets as his only way up. He is a magician, Benny tells us, whose “fingers transform / green bagged bud / into / green cash money.” For Lawson, drug dealing is not a moral failing but the most logical application of his skills in an environment offering few other opportunities. It provides him with money, status, and a sense of agency that a job “busing tables” never could. He lives by a simple, hedonistic philosophy: “Fuck later… All we got is now.” This rejection of the future is not nihilism, but a rational response from a boy who has never been given any reason to believe in one.

Ogle’s choice to tell this story as a novel in verse is the key to its devastating power. The form is not a gimmick; it is the very engine of the narrative. The short, staccato lines and the vast white space on the page create a sense of breathlessness and urgency, mimicking the racing thoughts of a teenager in a perpetual state of low-grade panic. Take, for instance, the opening sequence that frames the entire novel:

i’m waiting to die

the second

they kick in the door

—the drug dealer

and his crew—

’cause I know

it’s gonna be bad

’cause their

guns

are already out.

The verse forces the reader to experience the scene in fragmented, terrifying flashes. The single word “guns” on its own line gives it the weight of a physical blow. The white space surrounding it is the silence of held breath, the moment of pure, undiluted terror before chaos erupts. This technique is used throughout the book to distill complex emotions and situations to their elemental core. The narrative is not a linear progression but a collage of these intense moments, mirroring how memory itself works—not as a smooth film, but as a series of vivid, emotionally charged snapshots. By stripping the language to its essence, Ogle ensures that there is nowhere for the reader to hide. We are left alone with the characters in their most vulnerable moments, the starkness of the page reflecting the starkness of their reality. The entire book is, as Benny says on the second page, his life flashing before his eyes, and the verse format is the perfect medium for this frantic, tragic highlight reel.

Symbiosis and Sacrifice: The Foundation of the Bond

The relationship between Benny and Lawson is not born of simple proximity or shared interests; it is a survival pact forged in the crucible of shared trauma. The foundational event of their brotherhood occurs in third grade, a memory Benny recounts with the clarity of a sacred text. After being shoved to the ground by a bully taunting him about his absent father, a new kid, Lawson, intervenes:

Lawson walked up,

said, “My dad left too. Ain’t your fault. Dads suck.”

He offered his hand,

helped me up …

… then punched Donnie in the face.

This single, compact scene establishes the entire architecture of their decade-long dynamic. Lawson recognizes their shared wound—the paternal void—and immediately forms an alliance. His words, “Dads suck,” are a primal, unsophisticated creed that binds them more tightly than any formal oath. His actions define their future roles: Lawson is the protector, the one who acts, who meets the world’s cruelty with his own brand of violence. Benny is the one who is helped up, the beneficiary of this protection, the observer. Lawson’s punch is not just an act of defense for Benny; it is an act of defense for himself, a blow against the powerlessness they both feel. It is in this moment that they cease to be two lonely boys and become a single, symbiotic unit. As Lawson later tells him, “Brothers ain’t always made by blood. / Sometimes? / Sometimes, / brothers just find each other.”

This symbiosis is reinforced through a constant rhythm of mutual care, most powerfully symbolized by Benny’s car, the 1980 Cadillac DeVille he names María Carmen. The car is more than a vehicle; it is the physical space where their brotherhood is performed and reaffirmed. The recurring line, “I need a ride,” becomes Lawson’s mantra, a constant call that Benny always answers. Benny reflects on this duty with a simple, profound clarity:

i’m driving

my best friend

around town

’cause that’s what friends do.

Take care of each other.

Have each other’s backs

even when the world

doesn’t.

Benny’s role as the driver is both literal and metaphorical. He is the steady hand on the wheel, the one providing the means for Lawson to conduct his business, yet he remains physically separate from the act itself. This allows Benny to maintain the illusion of non-complicity, to believe he is merely “helping his friend” rather than acting as a getaway driver for a drug dealer. The car becomes a sanctuary, a rolling confessional, and a mobile crime scene. Inside María Carmen, they can be themselves, singing along to 2Pac, insulated from the judgments of the outside world. Benny’s act of driving Lawson is an act of love and loyalty, but it is also an act of profound enablement. Every trip deepens his complicity, tangling his destiny ever more tightly with Lawson’s, making it impossible to distinguish where one boy’s life ends and the other’s begins. Their bond, founded on the noble idea of “having each other’s backs,” slowly transforms into a pact where one is perpetually leading the other toward a cliff’s edge, with the driver’s hands firmly on the wheel.

The Divergent Trajectories: Education vs. The Street

As Benny and Lawson navigate the treacherous terrain of their late teens, the survival strategies that once united them begin to drive a wedge between their futures. Their paths diverge into two archetypal American narratives of escape: the long, arduous road of self-improvement through education, and the fast, perilous shortcut of the streets. This fundamental conflict between delayed gratification and immediate reward becomes the central tension of the novel, a constant tug-of-war played out in cafeterias, parks, and the worn leather seats of Benny’s car.

Benny’s path is dictated by his mother’s relentless ambition for him. “Education is everything,” she tells him, “And you’re going to college / if it’s the last thing I do.” For Benny, school is not a place of intellectual discovery but a battlefield where his future is won or lost. He internalizes this pressure completely, his life becoming a rigid cycle of school, homework, and his soul-crushing job at the diner. He sees this grind as the only legitimate way out. This commitment is contrasted sharply with Lawson’s worldview in a pivotal cafeteria scene. As Lawson counts a thick wad of cash from selling dime bags, he dismisses Benny’s legitimate work:

“Busing tables ain’t a real job.

Busing tables ain’t gonna get you no girlfriend.

Busing tables ain’t gonna put you through college neither.

Plus,

that shit

don’t pay shit.”

Benny’s silent response is devastatingly revealing: “I say, looking at my own Mexican brown skin, / kissed browner by the summer sun, / as I study while I eat.” In this brief, powerful moment, Ogle introduces the subtle but crucial element of race. For Lawson, who is white and charismatic, dealing is a high-risk, high-reward hustle. For Benny, a young man of color, the same actions would carry an exponentially greater risk of catastrophic consequences. He understands intuitively that he does not have the same margin for error as his best friend. His only option is the straight and narrow, no matter how demeaning or slow it may be. The “easy money” Lawson offers is a luxury Benny cannot afford, and this racial dynamic adds another layer of complexity and tragedy to their diverging paths.

The conflict is further illuminated through Benny’s tortured relationship with Lawson’s drug money. He is morally repulsed by it but pragmatically dependent on it for gas. This complicity gnaws at him until he finally confronts Lawson, refusing a payment by saying, “I don’t want your … you know … / drug money.” Lawson’s reaction is not anger, but a display of performative destruction that reasserts his control over their dynamic:

Lawson looks

like I hit him.

He takes the cash,

rips it in half,

lets it go,

bits drifting

to the ground

like autumn leaves.

…

“Either you take it, or I trash it.”

This act is a brilliant piece of psychological manipulation. By destroying the money, Lawson frames Benny’s moral stance as the cause of waste and absurdity. He forces Benny into a position where accepting the “drug money” becomes the lesser of two evils, the only way to prevent its destruction. Benny’s reluctant capitulation—”Fine. Next time, I’ll take it.”—is a critical turning point. It marks the moment he moves from passive enablement (giving rides) to active financial complicity. The image of the torn bills fluttering to the ground is a perfect metaphor for their fractured morality and the way their friendship, once a source of strength, is now a transaction that is slowly tearing them, and their values, apart.

The Escalation of Complicity and the Illusion of Control

A central tragedy of When We Ride is Benny’s persistent, and ultimately fatal, belief that he can remain insulated from the consequences of Lawson’s world. He operates under the illusion of control, convinced that as long as he is just the driver, as long as he doesn’t smoke, as long as he keeps his grades up, he can maintain a safe distance. He believes he can compartmentalize his life into “Benny the good student” and “Benny the loyal friend,” without acknowledging that the two have become one and the same. The novel’s second half is a systematic and brutal dismantling of this illusion, as Benny is dragged deeper into a world where his studiousness and good intentions are utterly irrelevant.

The point of no return arrives not with a bang, but with a quiet, terrifying violation. When Benny drives Lawson to his new supplier, Trent, he intends to wait in the car as usual, maintaining his carefully constructed boundary. This time, however, the boundary is breached. He is forcibly brought inside by a tattooed giant and subjected to a humiliating strip search to prove he isn’t wearing a wire:

Slow

I unbuckle,

unzip,

drop trou,

and let the linebacker

survey me, up and down.

…

“He’s clean,” he says

This scene is a chilling baptism into the true nature of Lawson’s business. The physical violation shatters Benny’s sense of safety and autonomy. In this dark, menacing living room, he is no longer Diego Benevides, the promising student ranked twelfth in his class; he is merely an anonymous associate of a low-level drug dealer, an object to be inspected for threats. The verse, stripped down to single, stark words (“Slow / I unbuckle, / unzip,”), forces the reader to experience his violation in agonizing real-time. This moment marks the death of Benny’s illusion. He can no longer pretend to be a passive observer. His body, whether he wants it to be or not, is now inextricably linked to the criminal enterprise. He is, in the eyes of this world, already guilty by association.

Despite this terror, Benny’s loyalty remains his fatal flaw. After every fight, every escalation, every near-miss, the gravitational pull of their shared history proves too strong to resist. The final ride is the ultimate testament to this tragic pattern. After a major falling out, Benny has finally, truly cut Lawson off. He has made the choice to save himself. But when Lawson shows up on graduation night—sober, apologetic, and appealing to their decade of brotherhood—Benny cannot maintain his resolve. Lawson asks for one last ride home, claiming, “I ain’t holding. / I took the night off.” It is a lie, but it is the lie Benny needs to hear to justify his capitulation. This decision leads them directly back to Lawson’s house and into the final, fatal confrontation with Trent. Benny’s last act on earth is the ultimate expression of their symbiotic pact. As Trent’s henchman aims a gun at Lawson, Benny acts on pure, unthinking instinct:

as

quick

as

a

bullet

I

shove

past

the

giant

and

jump

toward

my

brother

This is not a heroic choice; it is a reflex. It is the culmination of ten years of being Lawson’s protector, of “having his back,” a role reversal that proves deadly. The ending of When We Ride is devastating precisely because it is so inevitable. Benny’s death is the physical manifestation of a truth that has been present all along: in their two-person system, one could not survive without the other, but together, they were destined for destruction. He did not die for Lawson’s sins; he died because their lives were so enmeshed that a bullet aimed at one was, in reality, aimed at them both.

The Tyranny of the Dyad: Why Choice is a Bourgeois Illusion in ‘When We Ride’

At first glance, When We Ride appears to be a stark morality play about the consequences of individual choices. Lawson chooses the streets, Benny chooses loyalty, and tragedy ensues. However, to read the novel this way is to accept the comforting but facile American myth of absolute personal agency. A more profound and provocative reading reveals Rex Ogle’s novel as a powerful critique of this very myth. The central thesis of the book is not that the characters make bad choices, but that for boys like Benny and Lawson, “choice” itself is a bourgeois illusion, a luxury they were never afforded. They are trapped not merely by their socioeconomic conditions, but by the tyrannical, gravitational pull of their dyad—the two-person system of their brotherhood, forged in trauma and sealed by a desperate codependency from which there was never a viable escape.

Lawson’s path, in this framework, ceases to be a series of moral failures and becomes a rational, if tragic, response to his environment. He is presented with a clear dichotomy: the slow, humiliating, and low-paying “shit job” of the legitimate world, or the fast, empowering, and lucrative world of the drug trade. Given his natural charisma, his aversion to academic work, and the immediate financial pressure of supporting a mother who “can’t even get a job,” his decision to sell drugs is not an embrace of evil but an economic calculation. It is the most direct path to the things his society values: money, status (girls, new clothes), and the power to provide for his family. When Benny pushes him to get a “real job,” Lawson’s retort is painfully logical: “And it’ll take five times as long. / Or longer. / I need quick funds.” His life is a constant crisis, and the street offers the only immediate solution. His trajectory feels less like a choice and more like an inevitability, the logical outcome for a boy with his specific skill set and his specific set of limitations.

Benny’s tragedy is more complex because he is the one who believes he is exercising choice. He chooses to study. He chooses to work. He chooses to apply to college. He meticulously builds an escape route from the world that confines him. Yet, his every move is predicated on a single, non-negotiable axiom: his loyalty to Lawson. This loyalty is not a choice; it is a psychological imperative, the foundational principle of his identity established in third grade. Therefore, the one choice that could actually save him—severing ties with Lawson—is never truly available to him. Every time he attempts to pull away, the gravitational force of their shared history and Lawson’s deep-seated need for him pulls him back into orbit. He can choose to be a good student, but he cannot choose to abandon his brother. This makes his “good” choices tragically superficial. They are escape hatches on a submarine that is already taking on water. His fate is sealed not by his final decision to jump in front of a bullet, but by his thousand prior decisions not to walk away for good.

Thus, the entire narrative can be seen as the slow collapse of this two-body system. Their bond, which began as a source of mutual protection, curdles into a form of mutually assured destruction. Lawson needs Benny’s car and his stability to operate, trapping Benny in a cycle of complicity. Benny needs the sense of purpose and identity that comes from being Lawson’s keeper, a role that gives his otherwise anxious life a clear, if dangerous, mission. They are locked in a fatal embrace. The final confrontation with Trent is not an unlucky turn of events; it is the logical endpoint of the path they have been on for years. The gun is simply the mechanism that makes their emotional reality physical. When Benny dies, it is the physical manifestation of a spiritual truth: he could not conceive of a world where he lived and Lawson died. In the brutal calculus of their dyad, their fates were one. When We Ride is a tragic masterpiece precisely because it argues that the most powerful cages are not made of steel bars, but of love, loyalty, and a history that you can never outrun.

Riding Through the Broken Promises of Today

While When We Ride is a timeless story of brotherhood and fate, its pulse beats in frantic time with the anxieties of our present moment. To read this book in the 2020s is to see the faces of countless young men left behind by a nation of broken promises. It is a story that resonates profoundly in an era marked by “deaths of despair,” the hollowing out of rural and working-class communities, and a widening chasm between the haves and the have-nots that makes social mobility feel more like a fantasy than a plausible goal. Lawson Pierce is the ghost haunting the American heartland—a boy with potential and charisma, but with no legitimate outlet for his ambition, who turns to the underground economy of the drug trade not out of malice, but out of a desperate need for agency and dignity.

The novel serves as a powerful, ground-level corrective to simplistic narratives about crime and personal responsibility. It forces the reader to look beyond the act of drug dealing and see the systemic failures that create the dealer. Lawson’s story is a microcosm of a larger social tragedy: a generation of young people for whom the traditional markers of success—a steady job, a stable family, a path to the middle class—feel increasingly unattainable. In this context, the allure of “fast money” is not mere greed; it is a rational response to a system that seems rigged against them. The book quietly asks a devastating question: when society offers a young man nothing but a demeaning, minimum-wage job, can we truly be surprised when he seeks his fortune elsewhere? Ogle refuses to judge Lawson, and in doing so, he challenges us to extend the same empathy to the real-life Lawsons in our own communities.

Consequently, the ideal reader for When We Ride extends far beyond the traditional Young Adult audience. This is a necessary book for educators who see students like Benny and Lawson in their hallways every day. It is for social workers, policymakers, and anyone concerned with the plight of at-risk youth. It is a book that should be read by those who live in the comfortable, well-lit world of Lori and her family, as a window into the shadows where so many of their peers reside. But most importantly, it is for anyone who has ever had a friendship that felt like the whole world, a bond so intense it bordered on dangerous. It speaks to a universal truth about the way our earliest relationships shape us, and how the ghost of that one pivotal friend—the one who saved us, or the one we couldn’t save—walks with us for the rest of our lives.

The ultimate contemporary value of the novel lies in its unflinching emotional honesty. In an age of curated digital personas and performative success, When We Ride rips away the facade to expose the raw, messy, and often contradictory realities of growing up. It acknowledges that love and loyalty can be destructive forces, that the path to a better future is often paved with agonizing sacrifices, and that sometimes, despite our best efforts, we cannot save the people we love most. It offers no easy answers, no comforting platitudes. Instead, it offers something far more valuable: a moment of shared, heartbreaking truth. It validates the pain and confusion of its young readers while challenging its adult readers to look at the world around them with more compassionate, and more critical, eyes.

An Unforgettable, Devastating Coda

In the final analysis, When We Ride transcends its genre to stand as a towering achievement in contemporary fiction. It is a modern American tragedy that is as spare and brutal as it is beautiful and profound. Rex Ogle has crafted a novel that is not merely about the difficult choices of two teenage boys, but about the social and psychological forces that render choice a near impossibility. Through the relentless, percussive rhythm of his verse, he tells a story of a brotherhood that is both a life raft and an anchor, a source of salvation that becomes a sentence of death. The narrative is a masterclass in economy and emotional impact, where the empty space on the page speaks as loudly as the carefully chosen words, echoing with the unspoken fears, the desperate hopes, and the vast, lonely expanse of a future that will never be.

Ogle’s refusal to offer a simple moral is the book’s greatest strength. This is not a story about a “good” boy and a “bad” boy. It is the story of two boys trying to survive in a world that has failed them, armed only with a fierce, misguided, and ultimately fatal loyalty to one another. The ending, which could have been a simple, shocking climax, is elevated by a haunting coda—a final, brief chapter from Lawson’s perspective. We see him driving away, alone, haunted by Benny’s memory and grappling with the crushing weight of being the one who survived. This final note of grief and guilt transforms the novel from a cautionary tale into a profound meditation on loss and the impossible burden of moving forward.

When We Ride is a book that will leave a scar. It is a visceral, unforgettable reading experience that forces you to confront the ugliest parts of our social fabric and the most beautiful, terrible capacities of the human heart. The final question it leaves echoing in the silence is not whether Benny made the right choice, but whether a boy so defined by his love for another ever truly had a choice at all. The ride is over, its tragic destination reached, but the ghost of Benny and Lawson’s brotherhood will haunt the reader long after the final, devastating page has been turned. It is, without question, a masterpiece.

FAQ Section:

- Q1: What is the book When We Ride by Rex Ogle about?

- A1: When We Ride is a young adult novel in verse about the intense and ultimately tragic friendship between two teenage boys, Diego “Benny” Benevides and Lawson Pierce. It explores their divergent paths—one toward college, the other into the world of drug dealing—and the fatal consequences of their loyalty.

- Q2: How does When We Ride end?

- A2: The ending of When We Ride is tragic. During a confrontation with a dangerous drug supplier named Trent, Benny jumps in front of Lawson to save him and is shot and killed. The book’s final chapter is a poignant epilogue from Lawson’s perspective, reflecting on his grief and guilt as he leaves town to start a new life.

- Q3: Is When We Ride a true story?

- A3: While Rex Ogle draws on raw, authentic emotions and experiences common to many young people in difficult circumstances, When We Ride is a work of fiction. Its power comes from its realistic portrayal of friendship, poverty, and the pressures facing teenagers.

- Q4: Is When We Ride a good book for adults?

- A4: Yes, absolutely. While categorized as Young Adult, its profound themes of loyalty, social determinism, grief, and the complexities of male friendship make it a powerful and thought-provoking read for adults. Its sparse, poetic language and unflinching emotional honesty are hallmarks of great literary fiction.